Service Mesh Architecture and Components

Learn more about service mesh fundamentals in The Enterprise Path to Service Mesh Archictures (2nd Edition) - free book and excellent resource which addresses how to evaluate your organization’s readiness, provides factors to consider when building new applications and converting existing applications to best take advantage of a service mesh, and offers insight on deployment architectures used to get you there.

Service mesh architectures typically consist of three planes: a management plane, a control plane, and a data plane. The analogy between how physical networks (and their equipment) are designed and managed along with the concept of these three planes immediately resonates with network engineers. The OSI model is another type of training that network engineers receive. For those who haven't seen the OSI model in a while, Figure 1 serves as a refresher.

Figure 1: Physical networking versus software-defined networking planes

Let’s contrast physical networking planes and network topologies with those of service meshes:

Physical network planes

The application traffic created by hosts, clients, servers, and applications that use the network as a transport is contained in the physical network data plane (also known as the forwarding plane). As a result, data plane traffic should never have source or destination IP addresses that are assigned to network elements like routers and switches; instead, it should be originated from and delivered to end devices like PCs and servers. To forward data plane traffic as swiftly as possible, routers and switches use hardware chips called application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs). A forwarding information base is referenced by the physical networking data plane (FIB). A forwarding information base (FIB) is a basic, dynamic table that maps a media access control address (MAC address) to a physical network port, allowing traffic to be transmitted at wire speed (using ASICs) to the next device.

The physical networking control plane is the logical entity that is linked to router processes and functions and is responsible for generating and maintaining necessary intelligence about the state of the network (topology) and the router's interfaces. The control plane includes network protocols, such as routing, signaling, and link-state protocols that are used to build and maintain the operational state of the network and provide IP connectivity between IP hosts. As physical network control planes run in-band with network traffic, they are vulnerable to Denial of service (DoS) attacks, which can result in:

- Exhaustion of memory and/or buffer resources.

- Loss of routing protocol updates and keepalives.

- Slow or blocked access to interactive management sessions.

- High CPU utilization.

- Routing instability, interrupted network reachability, or inconsistent packet delivery.

The physical networking management plane is a logical entity that specifies the traffic used to access, manage, and monitor all network elements via protocols such as SNMP, SSH, HTTPS, and Telnet. All network provisioning, maintenance, and monitoring operations are supported by the management plane. Although control plane network traffic is handled in-band with all other data plane traffic, management plane traffic can be carried over an out-of-band (OOB) management network to enable separate reachability if the primary in-band IP path is unavailable (and create a security boundary). Restricting management plane access to devices on trusted networks is critical.

Physical networking control and data planes are tightly coupled and generally vendor-provided as a proprietary integration of hardware and firmware. Software-defined networking (SDN) has done much to standardize and decouple. OpenvSwitch and OpenDaylight are two examples of SDN projects. We’ll see that control and data planes of service meshes are not necessarily tightly coupled.

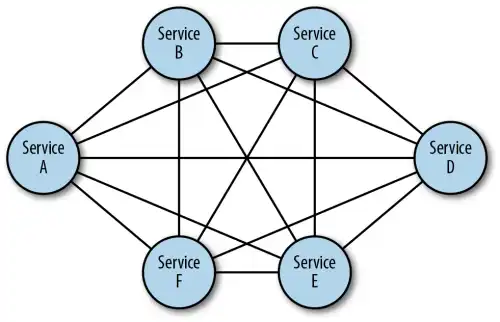

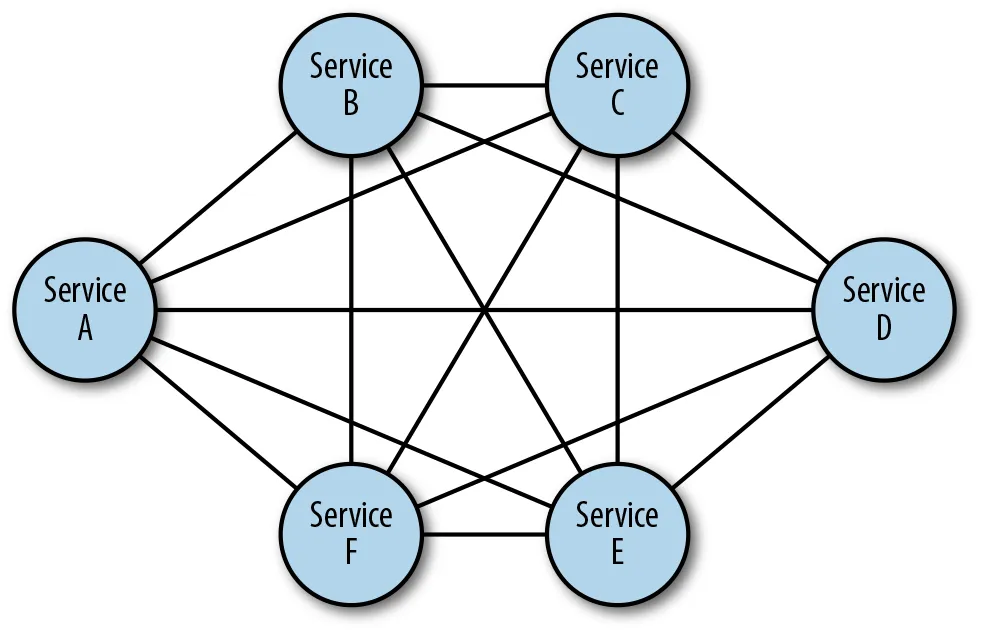

Figure 2: Mesh topology—fully connected network nodes

Physical network topologies

Star, spoke-and-hub, tree (also called hierarchical), and mesh are some of the most used physical networking topologies. Nodes in mesh networks connect directly and non-hierarchically, such that each node is connected to an indefinite number (typically as many as possible or as needed dynamically) of neighbour nodes, allowing at least one path from a given node to any other node to route data efficiently .

Wireless is the canonical use case for physical mesh networks in which the networking medium is sensitive to line-of-sight, weather-induced, or other disruptions, and so reliability is a top priority. Mesh networks typically self-configure, allowing dynamic task distribution. This ability is especially important to mitigate the risk of failure (improving resiliency) and reacting to continuously changing topologies. It's easy to see why this network topology is the preferred design for service mesh architectures.

Service mesh network planes

Service mesh architectures typically employ the same three networking planes: data, control, and management.

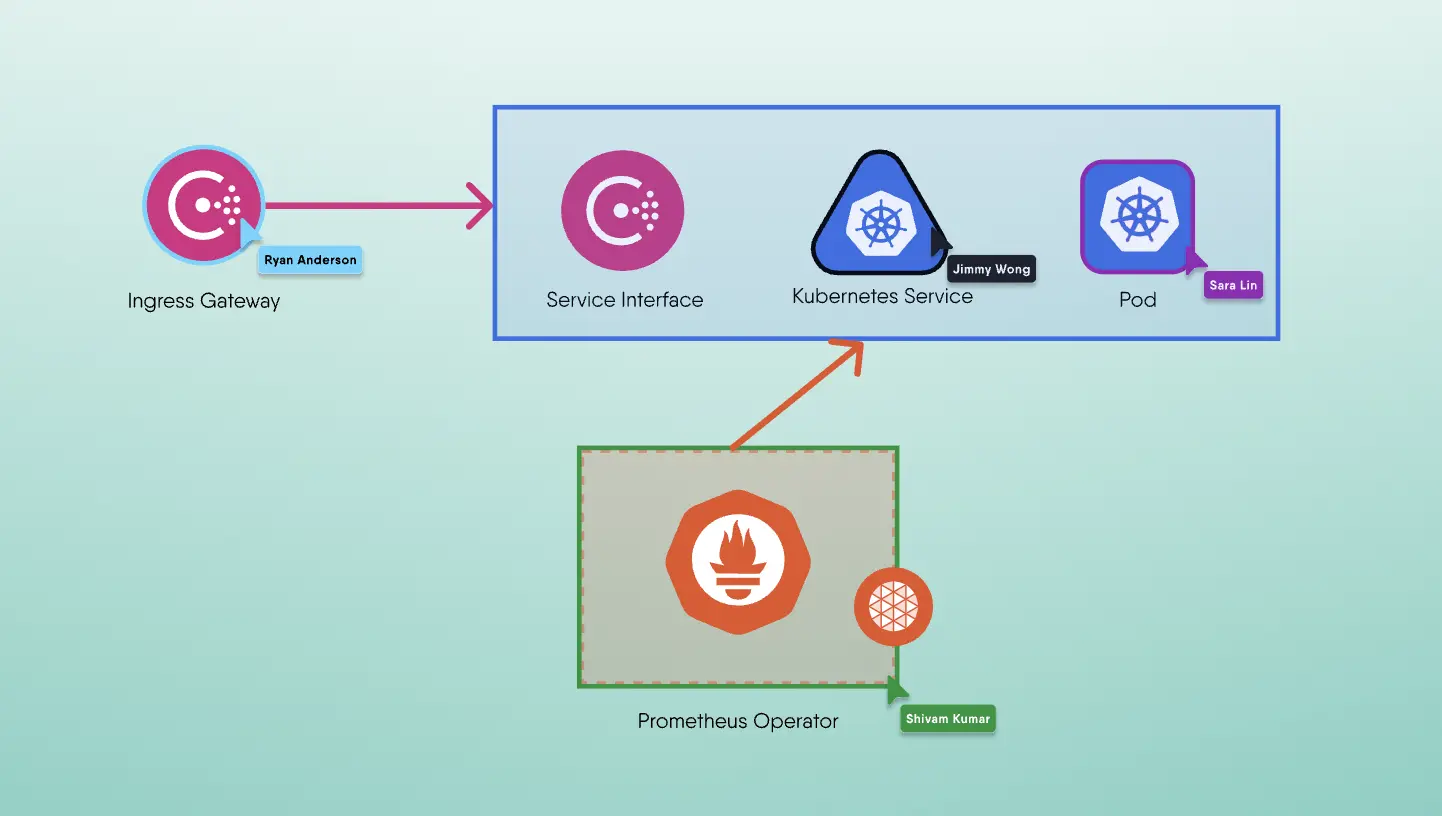

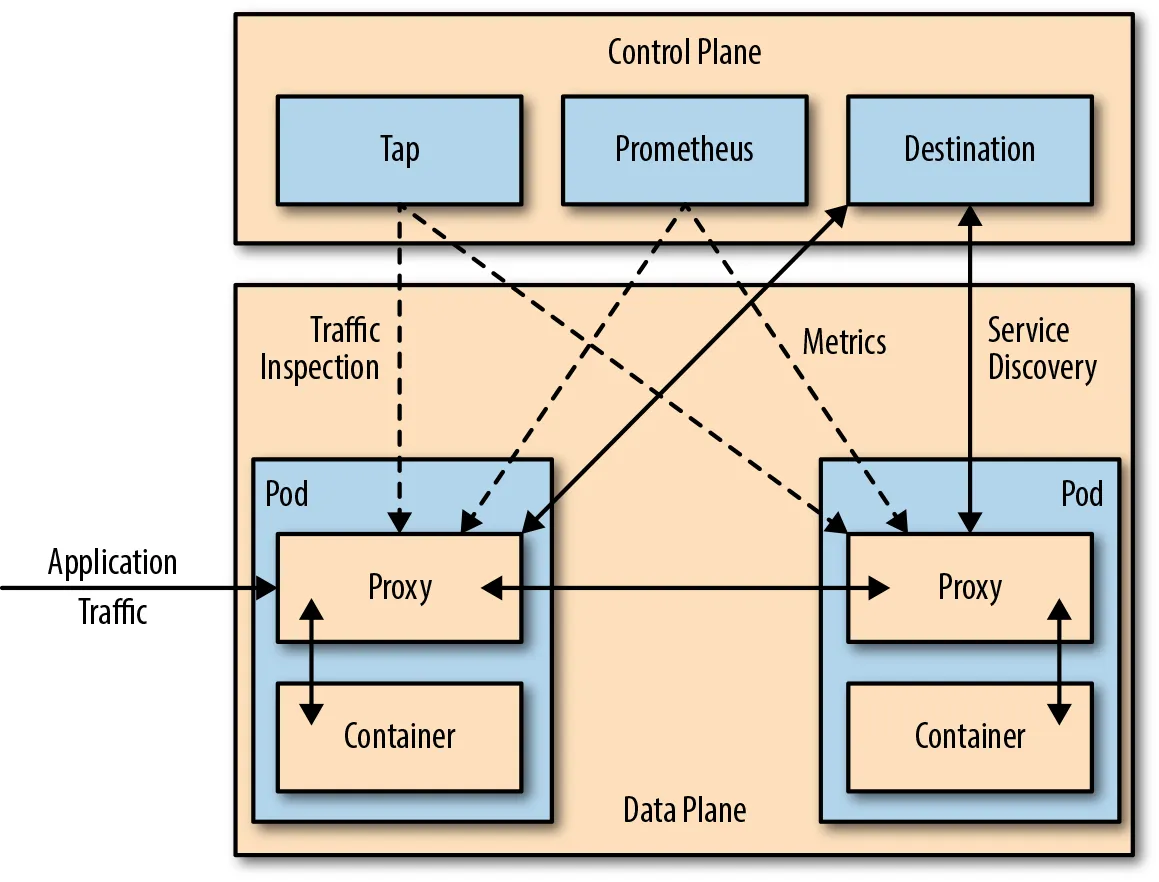

Figure 3: An example of service mesh architecture. In Conduit’s architecture, control and data planes divide in-band and out-of-band responsibility for service traffic

A service mesh data plane (also known as the proxying layer) intercepts all packets in a request and performs health checks, routing, load balancing, authentication, authorization, and generation of observable signals. Service proxies are transparently inserted, and applications are oblivious of the data plane's existence when they conduct service-to-service calls. Intra-service communication, as well as inbound (ingress) and outbound (egress) service mesh traffic, are handled by data planes. Whether traffic is entering the mesh (ingressing) or leaving the mesh (egressing), application service traffic is directed first to the service proxy for handling prior to sending (or not sending) along to the application. Traffic is transparently intercepted and redirected to the service proxy in order to reroute traffic from the service proxy to the service application. The service proxy intercepts and redirects traffic between the service proxy and service application places the service application’s container onto a network it would otherwise not be on. All traffic to and from the service application is seen by the service proxy. Service proxies are the building blocks of service mesh data planes.

The technology utilised to intercept and redirect traffic varies between service meshes. Some meshes allow you the option of using iptables, IPVS, or eBPF to transparently proxy requests between clients and service applications. Other service mesh proxies operate in a less transparent manner, requiring application traffic to be configured to direct their traffic to the proxy. The operating system type and kernel version used for the service mesh deployment are constrained by the choice of each of these technologies, which influences the speed with which packets are processed.

Envoy is one of the most widely used proxy in service mesh data planes. It's also common to see it deployed as a load balancer or ingress gateway. The proxies used in service mesh data planes are highly intelligent. In order to manipulate network packets (including application level data), they may include any number of protocol-specific filters . Extending data plane capabilities with technology advancements like WebAssembly allows service meshes to inject additional logic into requests while simultaneously handling large traffic loads.

When the number of proxies becomes unmanageable or when a single point of visibility and control is required, a service mesh control plane is essential. Control planes offer policy and configuration for the services in the mesh, transforming a set of isolated, stateless proxies into a service mesh. Control planes run out-of-band and do not directly touch any network packets in the mesh. Control planes usually include a command-line interface (CLI) and a user interface to interact with, both of which provide access to a centralised API for regulating proxy behaviour holistically. You can use the control plane's APIs to automate changes to its configuration (for example, using a continuous integration/continuous deployment pipeline), where configuration is generally version controlled and updated.

We can see how the data and control planes are packaged and deployed in Linkerd (pronounced "linker-dee") and Istio (pronounced "Ist-tee-oh"), two prominent open source service meshes. In terms of packaging, Linkerdv1 contains both its proxying components (linkerd) and its control plane (namerd) packaged together simply as “Linkerd,” and Istio brings a collection of control plane components (Galley, Pilot, and Citadel) to pair by default with Envoy (a data plane) packaged together as “Istio.” Envoy is often labeled a service mesh, inappropriately so, because it takes packaging with a control plane to form a service mesh.

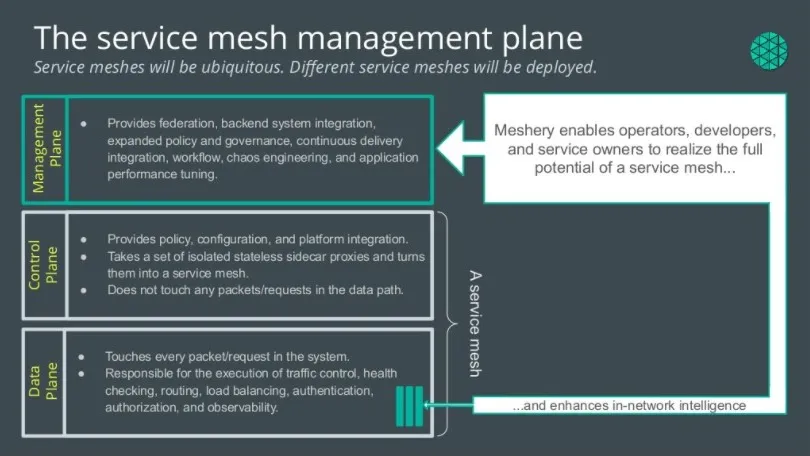

A service mesh management plane is a higher order level of control as shown in Figure 4. A management plane may provide a variety of functions. As such, implementations vary in their functionality: some focusing on orchestrating service meshes (e.g., service mesh lifecycle management) and mesh federation, providing insight across a collection of diverse meshes. Some management planes focus on integrating service meshes with business process and policy, including governance, compliance, validation of configuration, and extensible access control.

Figure 4: Meshery, the cloud native management plane’s architecture.

A service mesh management plane is a higher order level of control. A management plane can provide various functions. As a result, implementations differ in functionality, with some focused on orchestrating service meshes (e.g., service mesh lifecycle management) and mesh federation, which provides insight across a set of meshes. Some management planes focus on integrating service meshes with business process and policy, including governance, compliance, validation of configuration, and extensible access control.

In terms of deployments, data planes, such as Linkerdv2, contain proxies that are created as part of the project and are not designed to be configured by hand, but rather to have their behaviour completely controlled by the control plane. Other service meshes, such as Istio, prefer not to develop their own proxy and instead ingest and utilise independent proxies (separate projects), simplifying proxy selection and deployment outside of the mesh(standalone). Control planes are often deployed in a separate "system" namespace, using Kubernetes as the example infrastructure. Depending on how closely they integrate with non-containerized workloads and a business's backend systems, management planes are deployed both on and off cluster.