Choosing the Perfect Proxy

Historically, application delivery controllers were purchased, deployed, and managed by IT professionals most commonly to run enterprise-architected applications. With their distributed systems design and ephemeral infrastructure, cloud native applications require load balancers to be as dynamic as the infrastructure (containers, for example) upon which they run. These are often software load balancers. Because cloud native applications are typically developer-led initiatives in which developers are creating the application — that is, the microservices — and the infrastructure, developers and platform teams are increasingly making, or heavily influencing, decisions for load balancing (and other) infrastructure.

Selecting your proxy is one of the most important decision your team will make. A developer’s selection process gives heavier weight to a proxy’s APIs (due to their ability to programmatically configure the proxy) and on a proxy’s cloud native integrations (as previously noted). A top item on the list of demands for proxies is protocol support. Generally, protocol considerations can be broken into two types:

- TCP, UDP, HTTP: Network team-centric consideration in which efficiency, performance, offload, and load balancing algorithm support are evaluated. Support for HTTP2 often takes top billing.

- gRPC, NATS, Kafka: A developer-centric consideration in which the top item on the list is application-level protocols, specifically those commonly used in modern distributed application designs.

Tip: HTTP2, gRPC, NATS

At the heart of many distributed systems architectures are streaming and messaging protocols. When your applications need higher performance than JSON-REST, the application architecture commonly includes use of gRPC or NATS. REST is often found on the perimeter of the services while gRPC is used for service-to-service interactions. gRPC is a universal RPC framework. NATS is a multi-modal messaging system that includes request/reply, pub/sub and load balanced queues.

The reality is that selecting the perfect proxy involves more than protocol support. Your proxy should meet all key criteria:

- High performance and low latency

- High scalability and small memory footprint

- Deep observability at all layers of the network stack

- Programmatic configuration and ecosystem integration

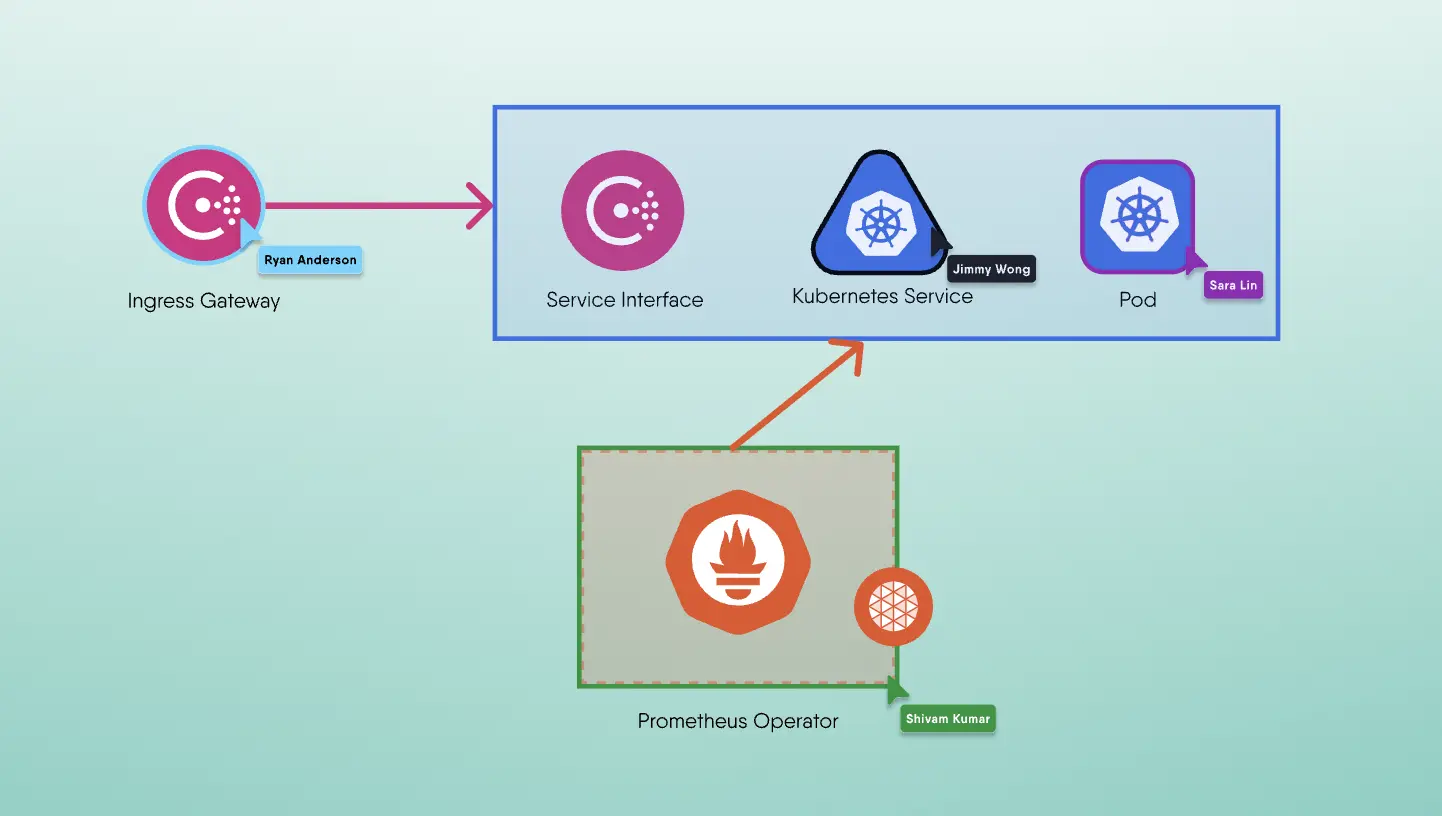

With a Kubernetes-native control plane, using CRDs and associated controllers enables powerful simplification, easy scaling, and intent-driven infrastructure. It is critical that the proxy has the capability to be intent-driven using Kubernetes CRDs and controllers (preferably an open source proxy like the Citrix Ingress Controller It’s the robustness of a proxy’s cloud native integrations and configuration APIs, like the Citrix Nitro API, that enables this. Not only are the proxy’s configuration APIs a key consideration, but so is the method by which they handle your applications’ APIs, specifically their security.

TCP/UDP Support

There are many applications that communicate over TCP/UDP ports. Kubernetes ingress was developed with web traffic in mind. It provides a standard way to control and route HTTP/S traffic into the cluster. However, ingress mechanisms for non-HTTP traffic are inconsistent and can be challenging.

Typical methods are:

Service.Type = Nodeport Nodeports use non-standard ports and are awkward and complex to get into production.

Service.Type = LoadBalancer Typically offered only in public clouds, LoadBalancers could get expensive depending on the number of services used.

Citrix offers Service.type = Loadbalancer with a built-in IP address manager that is consistent across clouds and on-premises deployments. This implementation simplifies IP address management and can save on load balancer costs in public clouds. An alternate method, also supported by Citrix, is to use ingress annotations that expose TCP/UDP ports.

All three methods make it much easier for TCP/UDP applications to be used as microservices without extensive code rewrites or protocol changes.

Securing Your Applications and APIs

API security considerations by traffic direction.

While traffic direction will dictate your security needs, the reality is that several concerns are shared considerations for both north-south and east-west traffic.

Let’s walk through the API security requirements one by one:

Ingress Security (North-South)

As services are exposed outside the cluster, the security considerations remain similar to those of monolithic deployments. In addition to ensuring protections like IP blacklist/whitelist and a robust encryption profile (SSL/TLS), it is imperative that the services are protected against both layer 3-4 and layer 7 DDoS.

Authentication/authorization are equally critical to ensure that the right access controls are established and maintained on data, APIs, and services. At the same time, as attacks are moving to the application layer, web application firewall (WAF) protections like SQL injection (SQLi), buffer overflow, and signature protections are table stakes. As the types of attacks are continuously evolving and because applications and APIs are changing many times a month, it is also critical that the protection mechanisms include behavior-based methods to automate the protection policies and detect potential zero-day attacks.

API Gateway and Security (North-South)

APIs are becoming the currency for digital transformation and for microservices that provide services via API, and therefore routing, security, control, and visibility for APIs is critical. API gateways are a perfect function to achieve these capabilities and typically are combined with the ingress solution.

API gateway solutions offer key functions like authentication, authorization, rate limiting, policy-based routing of APIs, and API versioning. In addition, the traditional controls applicable to a N-S web service are equally applicable and even more important to apply to APIs. API security is not just about authentication but also about ensuring that the content coming in from authenticated sources is not malicious. API gateway functions typically get configured in ingress through configmaps or CRDs.

Intra-Cluster Security for Service Mesh or Service Mesh-Lite (East-West)

Secure application deployment and secure infrastructure best practices dictate security controls in terms of both N-S and E-W service traffic (the former is generally more intuitively understood) because one layer of security isn’t enough, and in-depth defense is needed.

As the number and variety of your microservices expand, the pattern we’ve seen is that services might start as internal use only, but over time end up being exposed externally to customers and partners. The gooey center of your cluster, where you initially intend to have most of your service-to-service interactions, needs to be as secure because service-to-service interactions expand to those outside the cluster. Service meshes are a natural solution here. To obtain this added layer of security (and many other benefits), the adoption of service meshes is on the rise, dramatically. When your application delivery controller integrates with a service mesh, API security is broadly upleveled and guaranteed up to a certain point irrespective of developers' rigor in incorporating secure coding practices. That’s because a service mesh runs as a layer of your infrastructure, relieving developers of a number of (but not all) identity, authentication, and authorization concerns.

For example, inter-services communication should be mutually authenticated via transport layer security (TLS) so that only permitted API connections are allowed. Previously, this may have been implemented with each individual service, but the service mesh enables this functionality to be offloaded to a sidecar ADC, like Citrix CPX, and managed by the service mesh control plane.

Similarly, it should be possible to ensure a faster and more consistent approach to SSL policy in microservices environments through the use of SSL profiles. By defining acceptable SSL settings (for example, ciphers, protocol, and key strength) and binding them to your different entities, developers can quickly deploy consistent encryption policies that meet the appropriate security requirements. After all, isn’t the goal here to facilitate both developer velocity while ensuring that necessary security practices are met?

Another rapidly emerging technology to enable developer velocity is serverless computing. While serverless does indeed involve servers, it leverages infrastructure as code to run backend services as needed, which frees the developer from having to worry about scaling, patching, security, and infrastructure reliability. API gateways are key to applications built with serverless because the developer can simply specify policy such as authentication, authorization, and rate limits without worrying about the form factor, performance, and reliability of the proxy that usually provides these features.

Next, let’s explore aspects of another benefit use of a service mesh provides: traffic control.

Enabling CI/CD and Canary Deployment with Advanced Traffic Steering

Your application delivery solution should be an enabler of continuous delivery and canary deployments by providing advanced traffic steering. Intelligent proxies are required here. If you’re using a control plane (and not configuring the proxies directly), understand that you will only be able to harness the full power of your proxies to the extent that the control plane exposes their capabilities for configuration.

Canary Deployment

In order to facilitate canary deployments, you need a powerful proxy. Kubernetes facilitates rolling updates to a service deployment, focusing on ensuring that traffic shifting from one version of a service to the next happens gradually over time and with zero downtime. However, Kubernetes on its own doesn’t offer the level of granular control over traffic necessary for simply exposing your canary to a subset of users that you identify. Nor is it convenient for error rate and performance monitoring. Although performance monitoring is integral for canary analysis, many times the solutions for automated canary analysis are cobbled together.

A canary deployment is manual in that you will need to manually check that the canary behaves as you want before doing a full deployment (caution: the difference between canary and baseline isn't always clear). Robust application delivery solutions support automated canary analysis and progressive rollout. With an automated canary analysis, not only are you able to avoid manual administration of the deployment, but you can also rely on an automated statistical analysis to better detect problems in the set of metrics you’ve identified as indicators of a healthy deployment.

A/B testing requires full control over traffic distribution with several versions of your service running in parallel as you run various experimental tests. Experimentations often include measuring differences in conversion rates between versions of a service with the aim of improving a given business metric. To facilitate these experiments, you might want to direct requests based on various criteria like a client’s browser type and version or a user segment based on the presence of a specific cookie or the effect of UI changes on user behavior and the impact on overall performance.

Chaos engineering is akin to A/B testing in that it is an emergent practice that facilitates experimentation. Experimentation here is for purposes of testing and improving application delivery resiliency. Chaos engineering will evolve and expand in use as the complexity and rate of change of large-scale distributed systems demand new tools and techniques for increasing reliability and resiliency. Service-oriented teams (as opposed to infrastructure-oriented platform teams) will push past chaos engineering tools such as Chaos Monkey for inducing machine failures and skip Chaos Kong for evacuating entire regions. Instead they will move to application delivery solutions to perform precise service-level experiments on their path to improving application resiliency via orchestrated chaos. It's through exploration of the impact of increased latency and methodical failure of specific services that service teams will gain confidence in their systems’ capabilities to withstand turbulent conditions in production and begin to sleep more soundly at night.

Savvy cloud native engineers understand the nuances of these delivery methods, and the key role that the proxy plays in enabling these methods. Note, however, that the need for these methods is not restricted to cloud native workloads. These application delivery solution considerations generally apply to microservices and monolithic services in that irrespective of a given service’s architecture, new versions of the service need to be deployed and managed. Because we live in a hybrid world, we encourage you to seek application delivery solutions that do, too.

Achieving Holistic Observability

Observability is crucial for effective troubleshooting of microservices environments, but the ephemeral nature and complexity of distributed architecture presents serious challenges. It's incredibly hard to maintain awareness of what's happening in your environment when containers are continuously created and destroyed. Continuous deployment adds to the transient nature of containers because DevOps teams often push many new deployments per day to update their applications.

Similarly, the number of things to monitor — services, containers, users — is enormous, and the fact that everything is distributed makes microservices an incredibly complex environment. While it’s easy to determine if a service is down, troubleshooting slow applications is not? How can you isolate problems among all of the vast telemetry data to find the root cause, especially with inter-microservices (E-W) traffic?

You cannot monitor what you can't see. This is why it is vitally important to have inspection points through which the traffic passes. When they are correctly positioned, proxies/ADCs collect telemetry for an unprecedented view of application traffic — both N-S and E-W traffic across both monolithic and microservices architectures — and they report important data to collection tools.

To overcome the challenge of gaining observability into microservices, you need to build an observability stack. The stack should consist of four pillars: logging, metrics, tracing, and service graphs. However, these should not be viewed as individual, disjointed components but rather as a holistic observability stack that is integrated and can combine data as required.

LogsLogs are an immutable record of an individual event at a particular time. They are designed into systems, and there tends to be a log record to accompany almost every action. While logs are highly granular, they are limited in their searchability, and it is not usually feasible to process them manually. ADC feeds log data into tools like Elasticsearch for processing and indexing and Kibana for data visualization.

MetricsMetrics are data points that are measured over time that can be used to monitor trends and set alerts. In addition to the system resources of your individual proxies, the unique position of the proxies means that it sees important information about the use of the application - number of requests, HTTP request rate, errors and more. These metrics can be exported by ADCs to tools like Prometheus where they can be processed and tools like Grafana can visualize them, set alarms create heat maps to help you understand the status of your ADCs.

TracesThe flow of packets through a microservices-based application can be complex spanning multiple services (sometimes multiple times) so identifying why a service is slow can be difficult. Distributed Tracing is a technique that monitors request flow through microservices to build a map of the latency through each microservice hop. Trace is an end-to-end latency graph of a specific request. It represents the entire journey of a request and helps troubleshoot latency issues. Distributed tracing can also be used to understand the application architecture and services not being used. ADC integrates with open source tools like OpenTracing and Zipkin for distributed tracing

Service GraphsService graphs are dynamic graphical representations of microservices and their interdependencies. Service graphs, like that of the service graph in the Citrix Application Delivery Manager (ADM) console, provide detail on connectivity among microservices, help you identify issues via simple color coding, and learn composite health scores for each microservice based on throughput, saturation, errors, and latency. More than this, Citrix service graphs also have a built in DVR-like function, which allows you to zero in on the specific time period when an issue occurred.

Given their distillment of complex microservices into a graphical form, service graphs need to provide the ability to tag microservices and to use tags to search, sort , and filter. In this way, you can create custom service graph views of microservices running in production only or you can restrict your view to see details just for canary microservices.

As a complement to the basic pillars of observability (logs, metrics, and traces), service graphs enhance your observability stack. They provide a holistic view of your microservices-based application environments in a single place for an intuitive and convenient way to gain insight and troubleshoot microservices environments faster.

Managing Monoliths and Microservices

With hybrid cloud now a reality for many organizations, managing multiple environments with divergent capabilities and management systems is also a reality. Operating with confidence requires reconciling these differences into a uniform operational model and, subsequently, into a uniform understanding with consistent (read: quality) control. For operational consistency, you need a single pane of glass to manage your application delivery infrastructure across:

- Any application: monolithic and microservices-based applications

- Any environment: on-premises, public, private, and hybrid

- Any ADC form factor: physical, virtual, cloud, containers, sidecars, and more

You need holistic control and monitoring for operational consistency across all your workloads (new microservices and existing monoliths). Ideally, you’ll get such consistency from the proxy you’ve put in place. As you select your proxy, exercise caution when piecing together components from disparate vendors/projects into a solution, because this will not only require integration effort, but also separate specialization to understand and operate. The overhead of integration and specialization can be avoided when your proxy portfolio is robust and supports any application, any environment and form factor with operatonal consistancy.

Moreover, as the large public cloud providers extend their reach on-premises with offerings like Google Anthos, AWS Outposts, and Azure Stack, and as organizations adopt them as simpler paths to cloud migration, it becomes important to use a proxy that works in multiple environments. A battle-tested solution like Citrix ADC that is validated to work in Google Anthos and AWS Outposts environments both in the cloud and on-premises can be invaluable for maintaining operational consistency across your hybrid multi-cloud environment. Because Citrix ADC comes in a variety of form factors (including hardware, software, bare metal, cloud, containers, sidecars, and more) that are built on a single code base, it works across your hybrid workloads in a uniform fashion and prevents a sprawl of heterogenous load balancers across your environment.